Environmental Liability of Former Dry Cleaner Properties

By Keith Taylor, C.G., P.G. – Technical Lead & Senior Environmental Geologist at St.Germain Collins

Modern dry cleaning operations today follow strict rules to ensure that the common dry cleaning chemical tetrachloroethene (PCE) is properly managed and disposed of. However, from the 1930s when PCE was first used until the early 1980s, the environmental risks of PCE were not known and essentially had no regulatory requirements for handling and disposal.

Similar to the emerging contaminant PFAS, which has been in the news, PCE is resistant to degradation. Releases of PCE from decades ago remain an environmental liability in many urban locations.

PCE also is highly volatile and its vapors can be generated from contaminated soil or groundwater and migrate away from the source. In fact, the most common risk is for PCE vapor migration into buildings via cracks in the floor or gaps between the foundation and floor.

So how do you proceed with developing a property that was either formerly a dry cleaner or potentially adjacent to a former a dry cleaner?

dry cleaner or potentially adjacent to a former a dry cleaner?

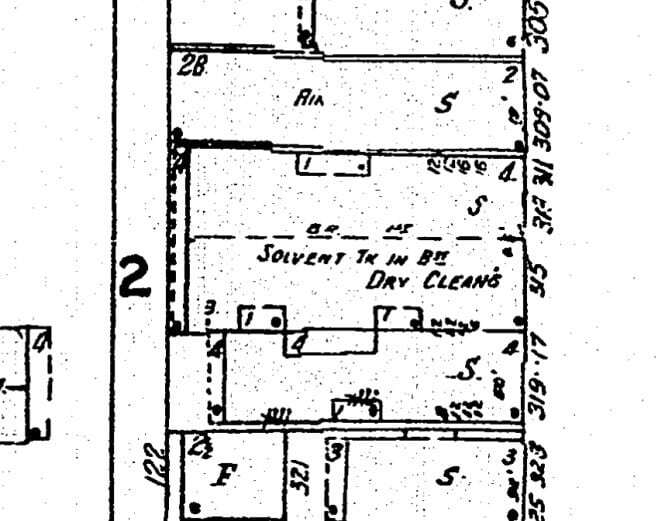

Environmental due diligence is a great first step, as it typically includes a review of the history of the subject property as well as abutting properties. Identifying former dry cleaners most often occurs through the review of historical data sources such as Sanborn Fire Insurance maps and city directories. The 1957 Sanborn map pictured at right identifies a dry cleaner in Lewiston with a solvent tank in the basement. PCE contamination was in fact found in soil vapor on the abutting property in 2018.

Another site in Westbrook was occupied by a dry cleaner until the 1960s when the building was demolished as part of urban renewal. A new building was constructed on the property in the 1970s, yet PCE was still detected beneath its basement floor nearly forty years later.

More problematic is when a former dry cleaner is not identified before the property is redeveloped.

A recent example occurred in Auburn, Maine where a 15-unit apartment complex was constructed in 1987 at the site of a former dry cleaner that operated from 1950 to 1986. It wasn’t until 2013 that the Maine Department of Environmental Protection (Maine DEP) sampled the soil vapor and indoor air and found high levels of PCE. The apartment building owner had nothing to do with the former dry cleaner, yet they will likely be responsible for investigation and remediation costs.

After reading these examples, anyone involved in real estate may reasonably conclude that former dry cleaner sites are to be avoided at all costs.

However, there are both technical and regulatory options that can eliminate the risk to human health and significantly reduce future liability.

First, PCE was described earlier as being very volatile. While this attribute can cause vapor migration into buildings, it also makes the removal of PCE beneath buildings relatively simple.

There are two approaches to removing PCE vapors from beneath existing buildings:

- installing a simple venting system similar to those used for residential radon removal; these systems require continuous operation for the lifespan of the building; or

- installing a soil vapor extraction system that more aggressively vents the sub-slab soil such that PCE levels permanently decline at which time the system can be turned off.

Both approaches are relatively inexpensive and have been employed for decades across the country. Periodic indoor air sampling is required during operation of either system.

For new buildings, a sub-slab vapor barrier can be installed during construction to prevent migration from below into the buildings.

With respect to environmental liability, the Maine DEP is very familiar with PCE-contaminated dry cleaner sites and the sub-slab venting systems. Under their Voluntary Response Action Program (VRAP), the Maine DEP can provide legally-based liability protections if the extent of the PCE contamination is adequately characterized and if an approved remediation system is installed.

Also keep in mind that PCE vapor beneath the floor does not necessarily mean vapor intrusion into the building is going to occur. Low levels of PCE or a “tight” floor and foundation can limit migration into a building such that a human health risk does not exist. In this situation, the Maine DEP VRAP would want solid documentation of this condition and commonly require that any new buildings be constructed with a vapor barrier.

Whatever the scenario, former dry cleaner sites can be redeveloped with no risk to human health and limited liability if the appropriate due diligence is completed.