Maine’s Housing Shortage Conundrum

By John Finegan | Associate Broker, The Boulos Company

Like many states across the country, Maine has a housing crisis. The ripple effects of COVID and the needs of asylum seekers have created an influx of people coming to Maine. Simultaneously, the average number of people per household is shrinking, and this exacerbates the demand for additional housing units. New construction is not going to solve the problem quickly, as construction hard costs are at all-time highs and developers find themselves quickly buried in complex bureaucratic processes and the attendant soft costs, which make construction harder and more expensive. Meanwhile, interest rates are the highest they’ve been since 2002, both increasing the cost of construction and decreasing what a buyer can pay for a home.

The housing crisis is a supply and demand issue. We have a lot of demand and not enough supply, and when that happens prices go up. MaineHousing has estimated that Maine needs 20,000 – 25,000 new housing units to meet demand, 9,000 in the Portland area. Until supply and demand are in equilibrium, we will continue to see housing prices increase.

The only way to end our housing crisis is to build more housing.

HOW DO WE BUILD MORE HOUSING?

Housing is built by for-profit developers (FPDs) and nonprofit developers (NPDs). NPDs finance their developments by leveraging federal, state, and local funds, including the low-income housing tax credit program. NPDs typically build affordable housing, creating housing for some of the most vulnerable people in our community. NPDs are limited, however, both by the amount of available funding and because the process for receiving those funds and tax credits is complex and requires a sophisticated developer.

To build more affordable housing, voters need to support policies and politicians that allocate more funds to NPDs as they did this past November across the country.

For profit developers typically do not take advantage of public funds. FPDs assess whether a project is worthwhile based on construction inputs and projected revenue. Construction inputs include hard costs (such as raw materials, labor, and land) as well as soft costs (such as engineering, permitting, legal, and accounting fees). Projected revenue is determined by estimating what a project will sell or lease for once completed. FPDs put these numbers into a proforma to estimate a return on investment for the project.

FPDs are constrained by the realities of the marketplace. They need to be able to give their financiers—banks, pension funds, private equity investors—an adequate return on their investment based on the risk profile and other investment alternatives. If they can’t, the project “doesn’t pencil,” they can’t get funding, and the project doesn’t get built.

To build more housing by FPDs, construction costs need to go down and/or projected revenue needs to go up.

HARD COSTS OF CONSTRUCTION

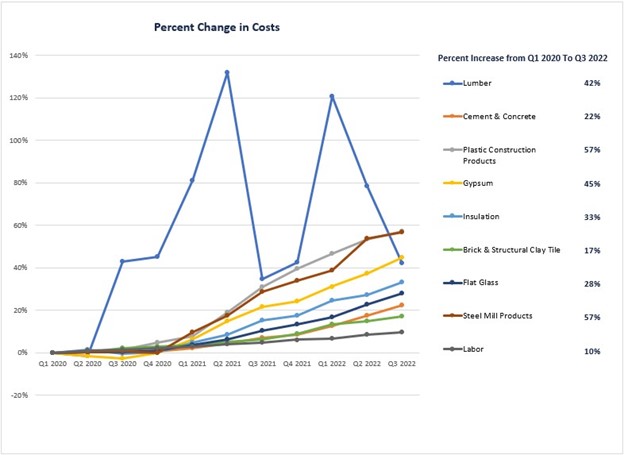

On average, the hard costs of construction increased 35% from January 2020 to September 2022. The increase in the cost of housing in new developments can be traced directly to this. Additionally, the volatility in hard costs has created a great deal of risk for developers, contractors, and sub-contractors who make decisions based on quoted prices with little assurance that those quote prices will be accurate once the costs are incurred. A labor shortage has also made staffing construction sites difficult. The unknowns of future construction prices and hard costs, coupled with uncertainty of labor, adds risk to any development which have killed several projects in Southern Maine over the past two years.

CONSTRUCTION HARD COSTS OVER TIME

The only way to lower these hard costs—or reduce their escalation—is for supply chains to normalize. In Q3 of 2022, hard cost escalations slowed and a recent study found that escalation should stabilize to 2–4% annual increases by 2023–2024. There is not much that we as individuals or as a community can do to control construction hard costs.

SOFT COSTS OF CONSTRUCTION

Soft costs are construction costs that are not related to raw materials, labor, or the physical building of the project. They include architectural drawings, environmental certifications, engineering studies, financing, legal fees, and any regulatory costs. Many of these soft costs are necessary. You can’t build a building without architectural plans, for example. However, some soft costs can be altered through policy. Fee-in-lieu costs, permitting fees, impact fees, etc. are government imposed costs that can be reduced or altogether removed to lower construction costs and allow more developments to be built. The June 2022 report by the National Multifamily Housing Council found that regulations imposed by all levels of government account for an average of 40.6% of multifamily development soft costs. None of this goes into actually constructing the units.

In Portland, a mandatory inclusionary zoning ordinance requires developers to make 25% of units in any 10+-unit development affordable, or pay a fee-In-lieu of $162,339 per affordable unit. This is effectively a tax of $40,585 per unit when the 25% requirement is spread across the entire project. It’s a prime example of how unnecessary regulatory costs can kill a housing project and discourage development.

The recent increase in interest rates also plays a substantial role. Higher interest rates increase the rates on construction loans, reduce the affordability of homes for buyers, and drive up the rents required to support a project.

LESS STICK

Developing housing is a numbers game, and projects must pencil to be built. Hard costs have gotten more expensive, but those are market realities and out of our control. Some soft costs, on the other hand, are unnecessary costs associated with regulations. Reducing or removing them can make housing creation less expensive and trigger new construction in the market.

Portland, Brunswick, Yarmouth, Freeport, Scarborough, South Portland, and Falmouth all have some form of housing regulation, either in place or being discussed. These policies have traceable, quantitative consequences, which make soft costs more expensive, killing projects. They also have a qualitative impact. Nationally, 47.9% of developers said they won’t even consider projects in jurisdictions with inclusionary zoning requirements, while 87.5% avoid working in jurisdictions with rent control.

MORE CARROT

Liberalization of zoning laws to allow for more density, taller height restrictions, smaller off-street parking restrictions, smaller impervious surface restrictions, and smaller setbacks allow developers to get more units onto the same amount of land. More units mean more revenue, and that means a greater likelihood that a project will make economic sense and be built. The Boston Fed’s New England Policy Center said that allowing more density, combined with relaxing height restrictions is the “most fruitful policy reform for increasing supply and reducing multifamily rents.” Economists from UCLA and the Legislative Analyst’s Office of California found that building new market rate housing lowers the cost of housing in cities for everyone.

In April 2022, Maine passed LD 2003 which will go into effect in July 2023. Once in effect, the bill will allow property owners to build accessory dwelling units in residential areas and allow up to two units on a lot zoned for single-family housing. For larger communities with designated “growth areas,” up to four units could be allowed. Additionally, the bill allows for a 2.5x density bonus for developers who hit affordability requirements.

It will be interesting to see how LD 2003 plays out in 2023. It may encourage developers to reevaluate developments based on the new density, and those developments may prove economically feasible and get built.

CONCLUSION

Westbrook, a town that has been welcoming towards developers, currently has 1,301 housing units in planning review. As of November, 2022, in Portland, where the fee-in-lieu effectively taxes 10+-unit developments, there are under 300 housing units in planning review. A clear slowdown has occurred since Portland increased its inclusionary zoning requirement in 2020. What does this tell us? Housing creators go where they’re wanted and where there are fewer economic barriers. If we want to be proactive in ending our housing crisis, local governments need to enact policies that incentivize development, not make it more expensive.

To end the housing crisis, more housing must be constructed. For more housing to be constructed, many things have to fall in line for projects to start making financial sense. Many of these factors are out of our control, but enacting policies that incentivize development is not.

Original article posted March 3, 2023, https://boulos.com/maine-housing-shortage-conundrum/